When Roads Become Traps and Rivers Turn Poisonous

There are countries where the biggest public debates are about economic policy or digital privacy. In India, we are still fighting for something far more basic —

Share on social media

About When Roads Become Traps and Rivers Turn Poisonous

The same headlines, the same grief, and the same sense of déjà vu. Families lose loved ones not to rare disasters but to something as ordinary and fixable as a pothole or an open manhole. And then we discuss these tragedies as if they were acts of god, not outcomes of administrative indifference.

The Bombay High Court, in High Court on Its Own Motion v. State of Maharashtra (2025), finally articulated what every citizen has been feeling for years. The judges said that “good and safe roads are an essential component of a meaningful life” and that the State’s failure to maintain them is nothing less than a violation of Article 21. That sentence doesn’t feel like legal reasoning — it feels like a sigh of collective exhaustion. After all, why should a nation racing towards high-speed connectivity lose people because a civic authority forgot to fill a crater in the road?

The Court’s frustration was unmistakable. It pointed out the “total lack of seriousness” among authorities and stated that unless individuals — actual officers, not nameless institutions — are held responsible, these deaths will keep repeating “every year”. And when the Court mandated ₹6 lakh compensation for every pothole death, it wasn’t just granting relief. It was issuing a warning that the value of a human life cannot be reduced to administrative paperwork.

This is not an isolated moment in Indian constitutional history. The Supreme Court, starting from Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978), has consistently expanded the meaning of the Right to Life beyond biological survival. The judges made it clear that living with dignity, safety, and wellbeing is a constitutional guarantee — not a privilege gifted by the government. Environmental and infrastructure negligence, therefore, fall squarely within the realm of fundamental rights violations.

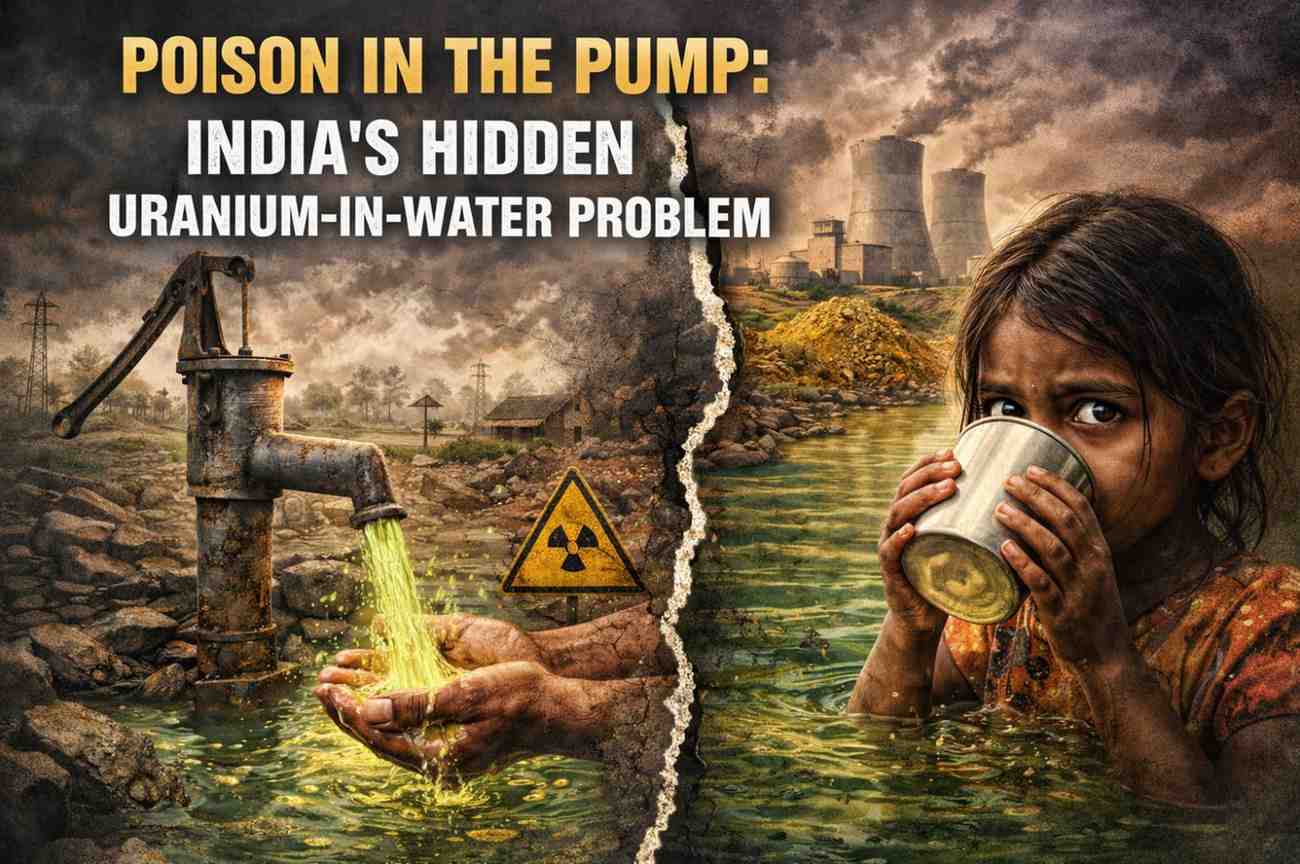

It was in M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (Oleum Gas Leak Case) (1986) that the Court declared hazardous conditions and environmental disasters as direct assaults on Article 21, ushering in the doctrine of absolute liability. Later, in Subhash Kumar v. State of Bihar (1991), the Supreme Court wrote with almost poetic clarity: “the right to live includes the right of enjoyment of pollution-free water and air.”

In today's India, that line feels painfully aspirational.

Our rivers are suffocating, our lakes are shrinking, and our cities breathe toxins.

The Supreme Court’s intervention in the recent Jal Mahal pollution matter — Jal Mahal Trust v. State of Rajasthan — shows how deep the crisis runs. Even after years of directives, authorities continued to allow untreated sewage to flow into a historically significant water body. The Court finally stepped in, stopping tourism and warning that repeated administrative failures can amount to a violation of the Right to Life itself.

Add to this the judgment in which the Court extended the Public Trust Doctrine to artificial water bodies — Maharashtra Housing Area Development Authority v. Gaikwad — declaring that the State is not a landowner but a trustee of natural resources. These rulings form a jurisprudential spine that repeats one message: when the government looks away as air becomes poisonous and water becomes undrinkable, it is not just failing in governance — it is breaching the Constitution.

And yet, the tragedies continue. Bridges collapse, roads cave in, and footpaths disappear under debris. Every such event becomes a 48-hour media story before fading into the background noise of accepted dysfunction. But behind each headline is a family that will never be the same. A child losing a parent to a pothole is not an “accident”. It is a slow, silent form of violence that comes from neglect.

This is why cases like Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India (1996) and A.P. Pollution Control Board v. Prof. Nayudu (1999) remain more important than ever. They articulated principles — the Precautionary Principle, the Polluter Pays Principle — that should have fundamentally changed how authorities behave. Instead, they remain beautifully written judgments followed by painfully familiar negligence on the ground.

The real crisis in India is not lack of laws or lack of court orders. It is the absence of urgency. The lack of accountability. The quiet acceptance that living in India means dodging potholes, breathing toxic air, and wondering if a bridge will hold your weight. But our courts have repeatedly reminded us that Article 21 is not a symbolic promise. It is enforceable. And it does not bend to excuses, budgets, or administrative laziness.

If our infrastructure continues to kill and our environment continues to deteriorate, the issue is not just civic failure — it is a constitutional wound. One that demands treatment, accountability, and above all, public awakening.

For only when citizens understand that safe roads and clean water are not privileges, but fundamental rights, will the system begin to shift. The courts have spoken. The Constitution is clear. Now it is time for the administration — and the nation — to listen.

Recent Posts

Can a Democracy Survive if It's Own Exec...

Read More

When Roads Become Traps and Rivers Turn...

Read More

Poison in the Pump: India’s Hidden Urani...

Read More

Aravalli Hills: When a Hill Has to Measu...

Read More

Men’s Rights in India — Finally Getting...

Read More

Some Words Get FIRs. Some Get Standing O...

Read More

India Rewrites the Rules of Work: Why th...

Read More

When the Files Became Too Heavy: A Saket...

Read More