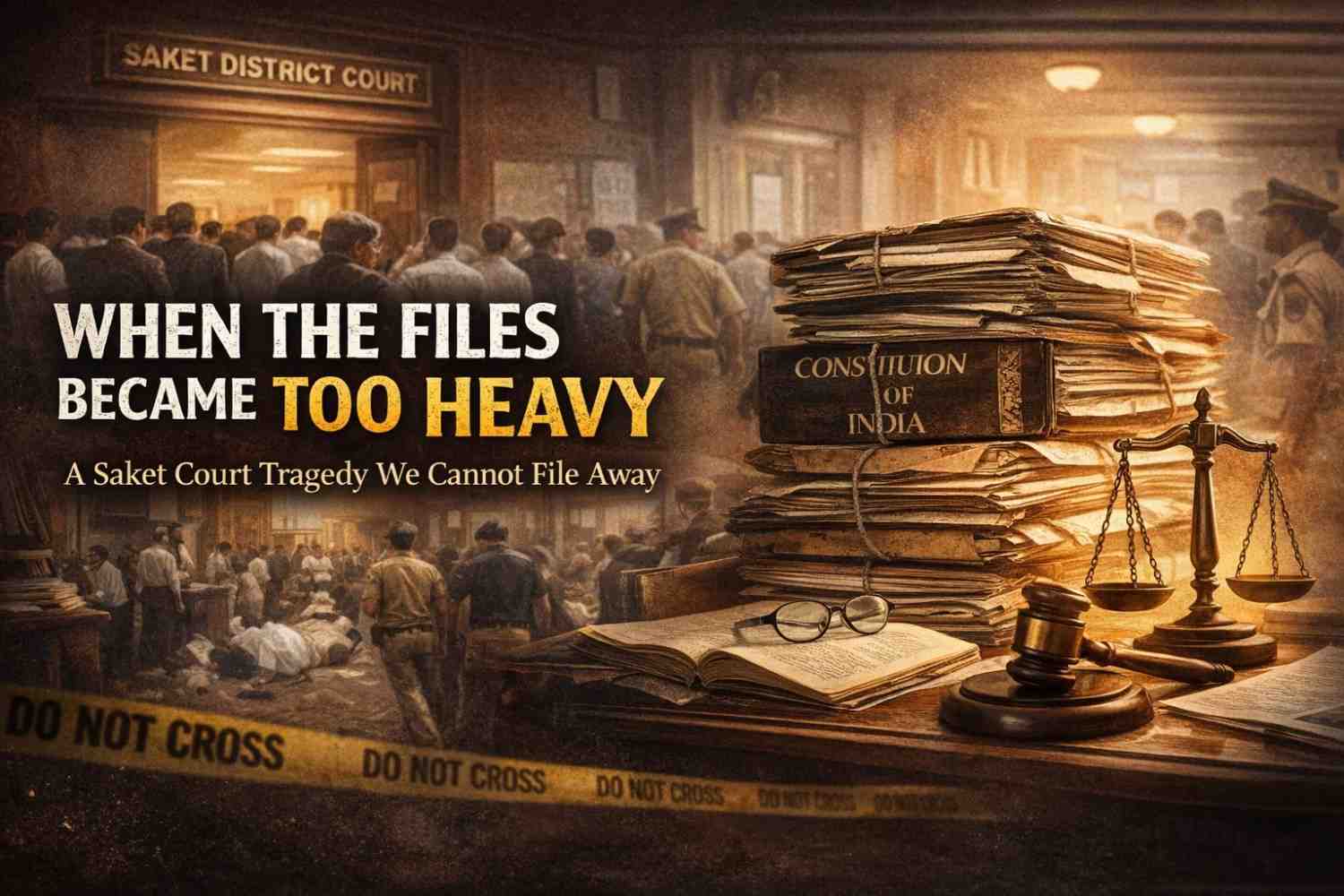

When the Files Became Too Heavy: A Saket Court Tragedy We Cannot File Away

Courts are meant to be places where justice is delivered, not where despair quietly accumulates behind case files. Yet, in January 2026, the Saket District Court complex in Delhi became the site of a deeply unsettling reminder that the justice system does not run on judgments alone — it runs on people. And sometimes, those people are pushed beyond endurance.

Share on social media

About When the Files Became Too Heavy: A Saket Court Tragedy We Cannot File Away

The death of an ahlmad — a court record-keeper who ensures that cases actually move — was not just an isolated personal tragedy. It was a structural failure, unfolding in plain sight, inside one of the busiest judicial complexes in the country.

“Justice delayed is often discussed. Justice overworked is rarely acknowledged.”

The Incident That Shook the Corridors of Saket

A 43-year-old court staff member, posted as an ahlmad at Saket Courts, died by suicide after reportedly jumping from the fifth floor of the court premises. A suicide note recovered by the police spoke of unbearable work pressure, mental exhaustion, and the inability to cope with mounting demands. What made the note even more disturbing was the acknowledgment that he was 60% physically disabled, yet continued to shoulder responsibilities meant for multiple staff members.

This was not a sudden breakdown. Colleagues later revealed that he had repeatedly sought relief — including transfer requests — which went unaddressed. Like many court employees, he was functioning in a system where silence is mistaken for resilience, and endurance is rewarded with more work.

The Invisible Backbone of the Judiciary

Ahlmads are rarely spoken about in constitutional discourse, yet they are indispensable to court functioning. They maintain case records, manage filings, coordinate listings, and ensure that judicial orders are actually traceable. When an ahlmad is overburdened, justice itself slows — not because of legal complexity, but because human capacity has limits.

Delhi’s district courts operate under staggering pendency. Lakhs of cases move through corridors designed decades ago, with staffing levels that have not kept pace with litigation growth. Digital courts were meant to ease pressure, but in practice, they often shift the burden downward — onto clerical staff expected to manage technology, records, compliance, and timelines simultaneously.

“The system moves fast on paper. People inside it don’t always keep up.”

Workplace Dignity Is a Constitutional Guarantee, Not a Courtesy

The Supreme Court has long held that the right to life under Article 21 includes the right to live with dignity, and that dignity extends into the workplace.

In Francis Coralie Mullin v. Union Territory of Delhi (1981), the Court observed that the right to life is not mere animal existence but includes the right to live with human dignity. Later, in Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India (1984), the Court expanded this principle to working conditions, holding that humane conditions of work are integral to constitutional life.

More recently, in Vikram Deo Singh Tomar v. State of Bihar (1988) and Consumer Education & Research Centre v. Union of India (1995), the Court explicitly linked occupational health, mental well-being, and dignity to Article 21, making it clear that institutional convenience cannot override human limits.

Applied to court staff, the message is unavoidable: a justice system that compromises the dignity of its own workers violates the very Constitution it exists to uphold.

Disability, Accommodation, and Administrative Blind Spots

The deceased staff member’s note specifically mentioned his physical disability. Under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, government employers are under a statutory duty to provide reasonable accommodation — adjusting workload, modifying duties, and ensuring that disability does not translate into disadvantage.

The Supreme Court in Vikash Kumar v. UPSC (2021) made it unequivocally clear that reasonable accommodation is not charity; it is a constitutional obligation flowing from equality and dignity. Denial of such accommodation, the Court held, amounts to discrimination.

When a differently-abled court employee is expected to perform the workload of multiple staff members, the issue is no longer administrative oversight. It is a constitutional failure.

Judicial Pendency and the Burnout Nobody Sees

India’s judicial pendency crisis is often framed in numbers — crores of cases, decades-long delays, judge-population ratios. What is rarely discussed is the human exhaustion beneath those statistics.

Judges face crushing dockets. Court staff face crushing logistics. When pendency rises, pressure flows downward. Clerks absorb deadlines, compliance burdens, and administrative chaos long before litigants see adjournments on cause lists.

Burnout in the judiciary is not confined to judges. It permeates the entire ecosystem — silently, steadily — until incidents like Saket force public attention.

“Backlog is not just about cases. It is about people carrying them.”

Protests, Solidarity, and a Rare Institutional Pause

Following the incident, court staff across Saket staged protests and candle-light vigils. Lawyers joined in solidarity, recognising that a collapsing support system ultimately affects litigants as well. The protest was not about blame — it was about acknowledgment.

A planned boycott was called off only after assurances from the Delhi High Court administration that staffing shortages, workload distribution, and welfare concerns would be reviewed. While this response showed institutional sensitivity, it also raised a troubling pattern: reform arrives only after tragedy forces a pause.

This Is Not About Blaming Judges — It’s About System Design

It bears repeating: this is not an indictment of judges. The judiciary itself operates under extreme stress. The issue lies in administrative inertia, outdated staffing models, and the assumption that institutional loyalty can substitute for human capacity.

Efficiency targets without welfare safeguards eventually turn institutions inward, consuming those who keep them functional.

What Must Change — Structurally, Not Symbolically

Meaningful reform requires more than compensation or condolences. It requires:

• Immediate filling of clerical vacancies

• Rational staff-to-case ratios

• Mandatory mental health support mechanisms

• Enforced disability accommodations

• Periodic audits of workload and infrastructure

These are not reforms against efficiency. They are reforms for sustainability.

Closing: Justice Is a Collective Effort

The Saket Court tragedy forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: justice is not delivered by judgments alone. It is carried by clerks, record keepers, and staff who ensure the system moves — often at personal cost.

A court that safeguards constitutional rights must first safeguard the dignity of those who serve it.

“A system built to hear everyone must also listen within.”

If this incident becomes just another closed file, the lesson is lost. If it becomes a turning point, then perhaps the system will finally recognise that justice cannot be efficient if it is inhumane.

Recent Posts

Can a Democracy Survive if It's Own Exec...

Read More

When Roads Become Traps and Rivers Turn...

Read More

Poison in the Pump: India’s Hidden Urani...

Read More

Aravalli Hills: When a Hill Has to Measu...

Read More

Men’s Rights in India — Finally Getting...

Read More

Some Words Get FIRs. Some Get Standing O...

Read More

India Rewrites the Rules of Work: Why th...

Read More

When the Files Became Too Heavy: A Saket...

Read More